| BACK PAGE |

Select Poems by John Keats |

NEXT PAGE |

John Keats by Amy Lowell

CHAPTER I

FROM BOY TO MAN

|

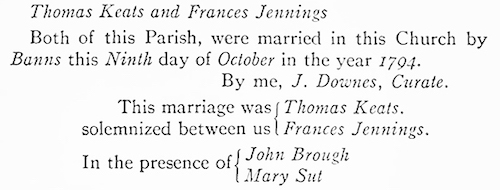

THE leaves were turning brown, and fluttering down in companies to be scuffled carelessly underfoot by passers-by in the squares, and parks, and graveyards—anywhere, in fact, where there were leaves to turn brown and fall. In the West End of London, shuttered houses gazed blankly at empty streets, except when caretakers flung open their wide doors and revealed glimpses of darkened halls echoing with emptiness. Drawing-rooms slumbered, swathed in cambric coverings. Rats scuttled unmolested across the floors of deserted stables. Footman's knock and postman's bell were events of rare occurrence. The West End, or rather that important part of it composed of strictly human elements, was scattered all over Great Britain: it cultivated its magnificent gardens in every shire in England; it killed exuberantly, bagging birds and beasts with unabatable ardour from Scotland to Land's End; it sipped and bathed and attended routs and concerts at Bath; or, if it happened to be in the Prince of Wales's set, briefly sojourned in the wake of that fantastic gentleman whither fancy led him, which on this particular Autumn, having just broken with Mrs. Fitzherbert, was not Brighton. But, whatever its temper, as it bumped and rolled in its own carriages toward its chosen destinations, the sight of broad fields and finely timbered parks caused it to thank its stars with fervour that the English channel separated it from France, still in the clutches of the Reign of Terror. Wherever the world of fashion might have betaken itself, it had betaken itself somewhere. The West End was deserted, and nowhere was its desertion more noticeable than it was of a Sunday in its favourite church, Saint George's, Hanover Square. But although the meagre congregation which gathered for its Sunday services could not boast a single denizen of the quarter, it was still, in the eyes of the parishioners of less favoured edifices, the most desirable church in all London to be married in. It was not uncommon for aspirants to matrimony from other parishes to hire rooms within the area of its jurisdiction and deposit bags or wearing apparel in them in order that its hallowed influence might shed its blessing on their marriage vows. This was snobbish, no doubt, but it also showed a praiseworthy desire to rise in the world, and was probably the reason, and very likely the method of procedure, which induced two young persons who lived in Finsbury to be married there. These persons were Frances Jennings, daughter of John Jennings, a livery-stable keeper at the sign of the Swan and Hoop, Finsbury Pavement, Moorfields, and her father's trusted head ostler, Thomas Keats. So they appeared to themselves; to us, they appear uniquely as the future father and mother of John Keats. If the choice of Saint George's as the scene of the wedding ceremony was for any other reason than that I have stated, I do not know what it was; unless, indeed, the marriage were in the nature of a runaway match owing to some objection on the part of the bride's parents, whose own notions of rising in the world may have taken another direction, but their evident sense of the probity of Thomas Keats, which as events prove was great, does not seem to point in this direction. However that may be, the marriage took place at Saint George's on Thursday, October ninth, 1794.  SAINT GEORGE'S, HANOVER SQUARE From a print in Ackerman's ''Repository of the Arts," 1812 Author's Collection The register of the church reads as follows:  Who John Brough and Mary Sut were, no one knows. They appear and disappear with their signatures. Their presence, and the absence of Mr. and Mrs. Jennings, gives some colour to the disapproval theory, but subsequent occurrences do not seem to bear it out. At any rate, the young couple returned to the Swan and Hoop, and there, one year later, their first son, John Keats, was born. There is some doubt as to whether October twenty-ninth or October thirty-first was his birthday. Everyone connected with Keats seems to have believed that he was born on October twenty-ninth, but in the baptismal register at St. Botolph's Church, Bishopsgate, where he was christened on December eighteenth, 1795, is a marginal note, said to be in the handwriting of the rector. Dr. Conybeare, stating that he was born on October thirty-first. This appears to me the flimsiest evidence, as the rector could know nothing of the matter except what he was told and may very possibly have mistaken what was said. Keats is supposed to have been a seven months child, but he seems to have suffered from none of the disabilities which usually hamper such children. For sixteen months, John remained the only child; but on February twenty-eighth, 1797, another son, George, was born; and on November eighteenth, 1799, still another, who was named Thomas after his father. Since these two brothers play a very large part in Keats's life, it is important to remember their relative ages. A fourth son, Edward, born in 1801, died in infancy, and the only girl, Frances Mary, did not arrive upon the scene until June, 1803. Of Keats's ancestry, we know next to nothing. The name is a fairly common one in England under various spellings, but all attempts hitherto made through baptismal registers, etc., to trace the origin of Thomas Keats, John's father, have failed. Sir Sidney Colvin says that, according to his information, Thomas Keats was born in 1768, but as he does not reveal the source from which he obtains this fact, we are almost as much in the dark as ever. The most plausible suggestion is that communicated by Mr. Thomas Hardy to Sir Sidney Colvin, and again mentioned in a letter to me from Mrs. Hardy. Mrs. Hardy's letter is a little fuller in detail than Sir Sidney's account, and the detail gives the matter a more likely possibility. Mrs. Hardy says that in her husband's youth "there was a family named Keats living two or three miles from here [Dorchester], who, Mr. Hardy was told by his father, was a branch of the family of the name living in the direction of Lulworth, where John Keats is assumed to have landed on his way to Rome (it being the only spot on this coast answering to the description). They kept horses, being what is called 'hauliers,' and did also a little farming. They were in feature singularly like the poet, and were quick-tempered as he is said to have been, one of them being nicknamed 'light-a-fire' on that account. All this is very vague, and may mean nothing, the only arresting point in it considering that they were of the same name, being the facial likeness, which my husband says was very strong. He knew two or three of these Keatses." An additional weight given to this suggestion is Severn's remark that, when he and Keats visited the spot identified as Lulworth in one of the many irritating delays to which wind-driven vessels were so often subjected and which tormented the passengers on the "Maria Crowther" for two weeks after sailing from Gravesend, Keats "was in a part that he already knew." We are not aware that Keats was ever in the neighbourhood, for Sir Sidney's idea that he may have broken the homeward journey from Teignmouth at Dorchester, and visited Lulworth Cove then, breaks down in face of an unpublished letter from Tom Keats that I shall quote in due course, in which he says that after leaving Bridport "we travelled a hundred miles in the last two days." This certainly leaves no time for sight-seeing, so that, if Severn be correct in thinking that Keats was familiar with the Lulworth "caves and grottoes," his familiarity must date from a boyhood visit of which we have no record, made perhaps while staying with relations. This is all mere guess-work, of course, but it is the nearest we can approach to a genealogy of the Keats family. Against this, is the statement of Señora Llanos (Fanny Keats) that she remembered hearing as a child that her father came from Cornwall, near Land's End. Again Sir Sidney is my authority, but again he neglects to mention his; so whether Señora Llanos's recollection is down in black and white somewhere, or is merely the product of hearsay remembrance on some one's part, we cannot tell. The origin of Keats's maternal grandfather is equally to seek. There is an entry of a marriage between a John Jennings and a Catherine Keate at Penryn, Cornwall, in 1770, and Sir Sidney Colvin conjectures that this entry may point to the fact of Jennings and his head man, Thomas Keats, being relatives; but Jennings is a usual patronymic enough in that part of Great Britain, and John is a name of no use at all for purposes of identification wherever English is spoken. What explodes Sir Sidney's conjecture into thin air, however, is the recently discovered knowledge that Mrs. Jennings was a Yorkshire woman.01 The present Keats family believe that Mr. Jennings was more than an ordinary livery-stable keeper. One of the granddaughters of George Keats remembers her grandmother to have said that he ran a line of coaches. I cannot pretend to have examined all the coach registers of the period, but he certainly was not one of the larger coach proprietors, as I can find no mention of him among these in the dozen or two volumes on the subject which I have consulted, therefore I think it more likely that he was one of the many jobbers who "horsed" someone else's coaches for a certain number of miles on their journey. That he was successful in his business is shown by his having retired with a competence. From an unpublished Memoir02 compiled by Keats's publisher, Taylor, after a conversation with Keats's quondam guardian, Richard Abbey, in 1827, and sent by Taylor to Woodhouse, we learn of Mr. Jennings that "he was excessively fond of the pleasures of the Table and 4 days in the week his wife and family were occupied in preparing for the Sunday's Dinner. He was a complete Gourmand." There is no doubt, however, as to the maliciousness of tone of Abbey's communications, and I think they must be taken with a grain of salt; but since they are the only ones we have concerning Keats's grandfather and grandmother, and are very open in dealing with the character of Keats's mother, they are of the utmost importance. Through this Memoir, we learn that Mrs. Jennings was a native of the village of Colne, at the foot of Pendlekill, in Yorkshire. Abbey came from the same village, and probably knew Mrs. Jennings from childhood. He seems to have been strongly prepossessed in her favour and gives an instance of her charitable disposition in befriending an unfortunate woman, also from Colne, and after the woman's death bestirring herself to succour her children. He does not seem to have liked her husband and appears to have almost hated her daughter, but whether his dislike — in the former case, at least — was well grounded or not, who can say. There seems to be no doubt that Mrs. Jennings was a good and worthy woman. George Keats, writing to Dilke in April, 1828,03 speaks of his grandfather Jennings as "extremely generous and gullible," but adds "I have heard my Grandmother speak with enthusiasm of his excellencies." He goes on to tell his correspondent that "Mr. Abbey used to say that he never saw a woman of the talents and sense of my grandmother, except my mother." Naturally George had never seen the Memoir written by Taylor after his talk with Abbey. But considering what Abbey permitted himself to say to Taylor about George Keats's mother on that occasion, George's letter to Dilke leaves us wondering who is lying. Is George attributing sentiments to Abbey which the latter never held in order to throw dust in Dilke's eyes, or had Abbey hypocritically said this to George, or was Abbey letting malice get the better of truth when he spoke to Taylor? The wisest course is to believe neither George nor Abbey implicitly, but to take a middle view between the two and suppose Keats's mother to have been a woman of strong passions and appetites, with no particular desire to curb either, but with something redeeming and attractive about her just the same. I have debated with some care the advisability of quoting what Abbey says of Mrs. Keats in this Memoir. But believing, as I do, that where so much has been told all should be recorded, realizing also that half truths never lead to fair conclusions, and that a great man can stand complete revelation; considering again that no adequate psychological study of a man's life and character can be made if we fail to take his inheritance into account, I have decided to quote the important parts of the Memoir in full, always cautioning my readers to notice that Abbey was undoubtedly exaggerating to a greater or lesser extent, and that he evidently gloated on blackening the character of Mrs. Keats whom he seems to have quite cordially detested. Here, then, is Taylor's paraphrase of Abbey's communications, continuing directly from the description of Mr. Jennings's love of eating: “His Daughter in this respect somewhat resembled him, but she was more absolutely the Slave of her appetites, attributable probably to this for their exciting cause. At an early Age she told my informant, Mr. Abby, that she must and would have a Husband; and her passions were so ardent, he said, that it was dangerous to be with her. She was a handsome, little woman. Her features were good and regular, with the exception of her mouth which was unusually wide. A little circumstance was mentioned to me as indication of her Character — She used to go to a Grocer's in Bishopsgate Street, opposite the Church, probably out of some liking for the owner of the Shop, — but the man remarked to Mr. Abby that Miss Jennings always came in dirty weather, and when she went away, she held her clothes very high on crossing the street, and to be sure, says the Grocer, she has uncommonly handsome Legs. He was not, however, fatally wounded by Cupid the Parthian.

But it was not long before she found a Husband, nor did she go far for him — a Helper in her Father's Stable appeared sufficiently desirable in her Eyes to make her forget the Disparity of their Circumstances, and it was not long before John Keats had the Honour to be united to his Master's Daughter."

After spattering Mr. Keats's character to the best of his ability — a spattering to which I shall have occasion to refer in a moment, but with its antidotes in the shape of less prejudiced accounts — Abbey describes his death with infinite malice and unveracity. The Memoir continues, in Taylor's words: "I think it was not more than 8 Months after this Event that Mrs. Keats again being determined to have a Husband, married Mr. Rawlins, a Clerk in Smith Payson and Co.'s — I know very little of him further than that he would have had a Salary of 700£ a year eventually had he continued in his Situation. I suppose therefore that he quitted it on becoming the Proprietor of the Livery Stable by his Marriage with Mrs. Keats, but how long the concern was carried on, or at what period Mr. Jennings died, or relinquished it, I didn't learn. It is perhaps sufficient to know that Rawlins also died after some little Time, and that his Widow was afterwards living as the wife of a Jew at Enfield, named Abraham." Here follows the account of Mrs. Jennings from which I have already quoted, and Taylor again returns to Mrs. Rawlings (for it was not Rawlins, as Taylor supposed) as painted by Abbey: "Her unhappy Daughter after the Death of her first Husband, became addicted to drinking and in the love of the Brandy Bottle found a temporary gratification to those inordinate appetites which seem to have been in one Stage or other constantly soliciting her. The Growth of this degrading Propensity to liquor may account for the strange Irregularities — or rather Immorality of her after-Life. I should imagine that her Children never saw her, and would hope that they knew not all her Conduct." We should hope not indeed, if this account of her were strictly true. That it is not, we can guess by the tone of it. Abbey had a good listener in Taylor, and he gave himself the luxury of speaking as he felt. Taylor, in spite of a certain shrewdness, seems to have been considerably gulled by Abbey's speciousness. Both the gulling and the shrewdness appear in this paragraph: "Abby is a large stout good-natured looking man with a great Piece of Benevolence standing out of the Top of his Forehead." [It was the age of phrenology.] "As he spoke of the Danger of being alone with Miss Jennings I looked to see if I discern any of the Lineaments of the young Poet in his Features, but if I had heard the whole of his Story I should have banished the Thought more speedily than it was conceived — never were there two people more opposite than the Poet and this good Man." We may banish the thought, too, not because Abbey had a "Piece of Benevolence" sticking out of the "Top of his Forehead," but because the idea is completely absurd. But we may thank Taylor for the suggestion since it carries a wide train of possibilities in its wake. Granted that where there is smoke there is fire, Mrs. Keats probably did have qualities leading her to indiscretions, it is not unlikely that she was at once over-sexed and under-educated; that she was weak in self-control seems evident, but what the Memoir goes far to show is that Abbey had received, or thought he had received, some injury from her, an injury which looks very much as though it were a snub. Was Abbey, a married man, unduly attracted by the exuberant young lady, and did he dare something which she resented? His false witness against her husband points to something of the sort. What is a respectable, middle-aged man doing gossiping with a near-by grocer on the subject of a young lady's legs? Something on the part of his caller must have led the grocer on to these revelations. Abbey was, I fear, spying upon Miss Jennings, trying to find out whom she did look upon since she would not look at him. It is not a pretty story, and the gusto with which Abbey related it to Taylor is greatly against him. When Abbey began to speak of things which Taylor knew about, Taylor found him inaccurate, as we can see by this sentence at the end of the Memoir: "There is the whole of what he told me respecting John Keats, excepting such particulars as I was better acquainted with perhaps than he himself." I shall have occasion to come back to the Memoir again, but not in this connection. Before judging Mrs. Keats, we should look at her through other eyes. George Keats, writing to Dilke in 1825,04 has this to say of his mother: "My mother I distinctly remember, she resembled John very much in the Face was extremely fond of him and humoured him in every whim, of which he had not a few, she was a most excellent and affectionate parent and as I thought a woman of uncommon talents, she was confined to her bed many years before her death by a rheumatism and at last died of a Consumption, she would have sent us to harrow school as I often heard say, if she could have afforded." Making all allowances for a son's enthusiasm, still this is clearly not the debauched woman depicted by Abbey. In a later letter, the one already referred to, of April, 1828, George contradicts this earlier statement in one particular, for he says: "I do not remember much of my mother," yet he strengthens his impression of her character by adding "but her prodigality, and doting fondness for her children, particularly John, who resembled her in the face." Cowden Clarke says05 that Mrs. Keats was "tall, of good figure, with large, oval face, and sensible deportment." She must have been about twenty-eight when Clarke first met her, having been born in 1775. From such very conflicting accounts as these, it seems not too difficult to reconstruct the character of Mrs. Keats. She was certainly a vivacious woman, fond of everything gay and lively, sensuous, ardent in pursuit of any aim, and clever beyond the majority of her sex and station; the sort of person, in short, only too likely to be misunderstood in the narrow circle of her acquaintance. That Keats got his sensuous vigour from his mother seems self-evident; that he sublimated her somewhat raw instincts through the medium of poetry into an ardour for sheer beauty, is a fact which should be easily understood by students of modern psychology. John loved his mother passionately, as is no wonder. He was her first born, and from George's account we can see that she lavished a very special love on him. Buxton Forman records that, during her last illness, John (presumably in some vacation from school) often sat up with her all night, seeing that she got her medicine at the proper times, preparing the nourishment prescribed for her, and reading novels aloud to her, and Clarke says that at her death, which occurred when John was fourteen, his grief was deep and bitter, so much so that in his desolation he hid himself under the master's desk. Poor little shaver, so pitiably unable to cope with his first great sorrow! Of Thomas Keats, John's father, we know somewhat more; although George, in the letter to Dilke already quoted, says he remembers nothing of his father except that he had dark hair. As Thomas Keats did not die until George was seven, this lack of all recollection is strange. It can only be accounted for by supposing Thomas Keats to have been very much engaged by his business. Cowden Clarke has left us a very careful portrait of him, however. Clarke speaks of him as "a man of so remarkably fine a commonsense, and native respectability, that I perfectly remember the warm terms in which his demeanor used to be canvassed by my parents after he had been to visit his boys. John was the only one resembling him in person and feature." And elsewhere Clarke says: "I have a clear recollection of his lively and energetic countenance, and particularly when seated on his gig and preparing to drive his wife home after visiting his sons at school." Clarke was apparently wrong as to feature, for George may be trusted to know whether or not John took after his mother in that respect, unless his remembering only that his father had dark hair indicates that he had quite forgotten what he looked like. But the rest of Clarke's description is undoubtedly correct. Thomas Keats was a short, powerfully built man, like his eldest son, with an ambition and perseverance above the average and with a good mind. Now that we know how Thomas Keats impressed people of the type of Clarke's father and mother, we may return to the Memoir and see Abbey's malice in full swing, and also deduce, through his prejudice, a little more of the character of Keats's father. To Abbey's jaundiced eyes, Thomas Keats "did not profess or display any just Accomplishments. Elevated perhaps in his notions by the Sudden Rise in his Fortunes he thought it became him to act somewhat more the Man of Consequence than he had been accustomed to do — but it was still in the way of his Profession — He kept a remarkably fine Horse for his own Riding, and on Sundays would go out with others who prided themselves on the like Distinction, to Highgate, Highbury, or to some other place of public Entertainment for Man and Horse. — At length one Sunday night, he was returning with some of his jolly Companions from a Carouse at one of these Places, riding very fast, and most probably very much in Liquor, when his Horse leaped upon the Pavement opposite the Methodist Chapel in the City Road and falling with him against the Iron Railings so dreadfully crushed him that he died as they were carrying him Home." Abbey distorts facts with a diabolical cleverness. Thomas Keats did die from his horse falling with him, but he lived for seven hours at least after the event. He had been dining out, at Southgate, but where was the harm of that? There is no reason at all to suppose that he was drunk, that is a pure invention of Abbey's, for even he ushers in the statement with a "most probably." Why should not a stable-keeper ride a good horse? In those days, everyone who could kept a good riding horse, many men still preferring to make journeys on horseback rather than in a vehicle. Thomas Keats dealt in horses; they were not a luxury, but part of his business stock. That he displayed many "just Accomplishments," is proved by Clarke's remembrance of him. Yet, with all the falsity of accent in Abbey's account, one trait in Thomas Keats's character stands out clearly: his ambition to better his condition, to rise in the world. He was no "helper" in the stable, as Abbey insinuates, but the foreman of the establishment, at the time of his marriage; and when he kept the fine horse which so annoyed Abbey, he had become, by the retirement of his father-in-law, its ostensible proprietor. Bettering his condition was apparently one of the dearest wishes of his heart, and there is no reason to suppose that he wished only the froth of such betterment. The frill of being married at Saint George's need not blind us to the realization that beneath it lay both a refined taste and a solid appreciation of the value of education and good manners. Thomas Keats was civilized beyond his class, or endeavoring to become so — and what is strange in that, seeing he was the father of John Keats? How Keats came by his poetry has been a wonder to all his biographers. But we know more of the workings of the subconscious brain and the whys of genius than the then state of science permitted most of them to do. Mrs. Keats was passionate and weak; Thomas Keats was, or appears to have been, strong; the grandmother Jennings was certainly a woman of good sense. That there was intellect somewhere, must have been the case; at any rate, there was admiration of intellect, or Mr. and Mrs. Keats would not have considered sending the boys to Harrow, as George Keats says they did. Harrow meant not only a classical education, it meant association with boys of a better class than their own. But this is only snobbishness to a half-vision, there is plenty of evidence that Thomas Keats's snobbishness was the shell of an ideal. Here, in father, mother, and grandmother, are a series of inheritances which may well have produced a poet. Even imagination plays a part, for what was the ideal but an imagined one? Such a high reach for their sons shows an almost fantastic fancy on the part of both father and mother, and a fancy they were willing to abide by. Keats refined upon the imagination as he refined upon the passion, and his intellectual strength forged for both a medium of expression. In other words, character in his case made for creation. This is no new thing; everyone knows that the artist's temperament without the artist's power to create fills our sanitariums with neurotics. Reading between the lines of Abbey's Memoir, it seems likely that Mrs. Keats verged toward this state in her later years; but, poor creature, difficult as she may have been to her family, she did her son an infinite service. Her sympathy with John proves potentialities that she fatally lacked the power of turning into facts. What she had not, strength of character, her husband had, and between them they made their son, transmitting to him much that was unfortunate, it is true, but dowering him with the uncomfortable treasure of genius. Yet there is one question which no probing will satisfactorily answer: Why is there no mention of his parents in any of Keats's letters, even in those to his brothers and sister? There is but one exception to this throughout the correspondence, but the connection in which it occurs is most significant. Writing his third letter to Fanny Brawne from Shanklin, Keats seals it with an old seal of his father's, which he comments upon in this way: "My seal is mark'd like a family table cloth with my Mother's initial F for Fanny: put between my Father's initials." We have no other evidence of Keats's having used this seal, although, of course, he may have done so, but the reason for his using it here is obvious. Keats attached a good deal of weight to seals, as we shall see later. He could speak to Fanny Brawne as he could to no one else, naturally; the jest about the table-cloth is to ease an overflow of tenderness, and in his situation a "family table cloth" was not without meaning. Leigh Hunt says06 that Keats never spoke of the livery-stable, and thinks it was "out of a personal soreness which the world had exasperated." If this suspicion of Hunt's be correct, the less man Keats. Let us not seek our answer too far, with Abbey's ugly communication staring us in the face, but even supposing that it contains some grains of truth, Keats's reticence is more likely to have been caused by a feeling of sacredness toward his dead parents than to any sudden revelation of regrettable traits in his mother's character. Knowing how much he loved her, we may suspect a grief with which harness buckles have nothing to do, and a bereavement too deep to be chattered about. To Be Continued ... |